Working with Files and Directories

Last updated on 2025-04-01 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How can I view and search file contents?

- How can I create, copy and delete files and directories?

- How can I control who has permission to modify a file?

- How can I repeat recently used commands?

Objectives

- View, search within, copy, move, and rename files. Create new directories.

- Use wildcards (

*) to perform operations on multiple files. - Make a file read only.

- Use the

historycommand to view and repeat recently used commands.

Working with Files

Wildcards

Navigate to our prodinfo454 directory:

We are interested in looking at the sequencing runfolders in this directory.

There are a lot of directories! The directories were created to be programmatically searchable so they follow a specific format: R_<year>_<month>_<date>_<hour>_<min>_<sec>_<machine_name>_<machine_operator>_<run_name>

We can list all runs from 2012 using the command:

OUTPUT

R_2012_03_13_15_18_05_crinkle_DRobbins_DR031312lastRun646704:

aaLog.txt

R_2012_03_15_14_41_54_crinkle_DRobbins_DR031512Run760581:

aaLog.txtThe * character is a special type of character called a

wildcard, which can be used to represent any number of any type of

character (zero or more). Thus, R_2012_* matches every

directory that starts with R_2012_.

Notice that ls lists each directory and the files in the

directory. To show just the directories that match your search (and not

show the directory contents), add the -d (aka. directories)

flag.

OUTPUT

R_2012_03_13_15_18_05_crinkle_DRobbins_DR031312lastRun646704 R_2012_03_15_14_41_54_crinkle_DRobbins_DR031512Run760581You can also use wildcards on either end of your search (or both). Here we search for all runs on the machine “seabiscuit”:

OUTPUT

R_2009_02_09_15_29_04_seabiscuit_levesque_SPG3kbDevRun705303

R_2009_03_16_13_49_01_seabiscuit_pfrere_march16tworegionRUN636092

R_2009_04_03_12_42_34_seabiscuit_levesque_DrocksLastRun647068

R_2009_04_09_14_23_35_seabiscuit_AHolling_krocksfirstRun713432

R_2009_04_15_14_29_08_seabiscuit_AHolling_Kamran041509run712591

R_2009_05_15_13_55_34_seabiscuit_AHolling_BacEscEscEscRun646819lists only the directories with seabiscuit in the

directory name.

What do you think this command will do?

OUTPUT

/usr/bin/gettext.sh /usr/bin/lprsetup.sh /usr/bin/setup-nsssysinit.sh

/usr/bin/lesspipe.sh /usr/bin/rescan-scsi-bus.sh /usr/bin/unix-lpr.shLists every file in /usr/bin that ends in the characters

.sh. Note that this output displays full

paths to files, since each result starts with /.

Exercise

Do each of the following tasks from your current directory using a

single ls command for each:

- List all of the files in

/usr/binthat start with the letter ‘c’. - List all of the files in

/usr/binthat contain the letter ‘a’. - List all of the files in

/usr/binthat end with the letter ‘o’.

Bonus: List all of the files in /usr/bin that contain

the letter ‘a’ or the letter ‘c’.

Hint: The bonus question requires a Unix wildcard that we haven’t talked about yet. Try searching the internet for information about Unix wildcards to find what you need to solve the bonus problem.

ls /usr/bin/c*ls /usr/bin/*a*ls /usr/bin/*o

Bonus: ls /usr/bin/*[ac]*

Our data set: FASTQ files

Now that we know how to navigate around our directory structure,

let’s start working with our sequencing files. We did a sequencing

experiment and have two results files, which are stored in an

untrimmed_fastq directory.

Using the commands we’ve learned so far, we’re going to navigate to a

different filesystem. Starting from the root directory, we’re going to

‘broad’ instead of ‘home’. This filesystem is called /broad/hptmp (for

high performance temporary). /broad/hptmp

is available for Broadies who need a temporary space to do high

performance computing work. Files in /broad/hptmp are automatically

deleted after 14 days. We’ve created a computing_basics

directory for today’s workshop.

Let’s navigate to the untrimmed_fastq directory in

/broad/hptmp/computing_basics.

Download untrimmed_fastq.zip to your home directory and

unpack it.

BASH

$ cd

$ wget https://github.com/jlchang/cb-unix-shell-lesson-template/raw/main/learners/files/untrimmed_fastq.zip

$ unzip untrimmed_fastq.zipThen, in the following instructions, wherever you see

/broad/hptmp/computing_basics substitute

~/untrimmed_fastq.

Exercise

echo is a built-in shell command that writes its

arguments, like a line of text to standard output. The echo

command can also be used with pattern matching characters, such as

wildcard characters. Here we will use the echo command to

see how the wildcard character is interpreted by the shell.

OUTPUT

SRR097977.fastq SRR098026.fastqThe * is expanded to include any file that ends with

.fastq. We can see that the output of

echo *.fastq is the same as that of

ls *.fastq.

What would the output look like if the wildcard could not be

matched? Compare the outputs of echo *.missing and

ls *.missing.

Later on, when you learn to string together Unix commands, echo can be useful for injecting desirable text where you need it.

Command History

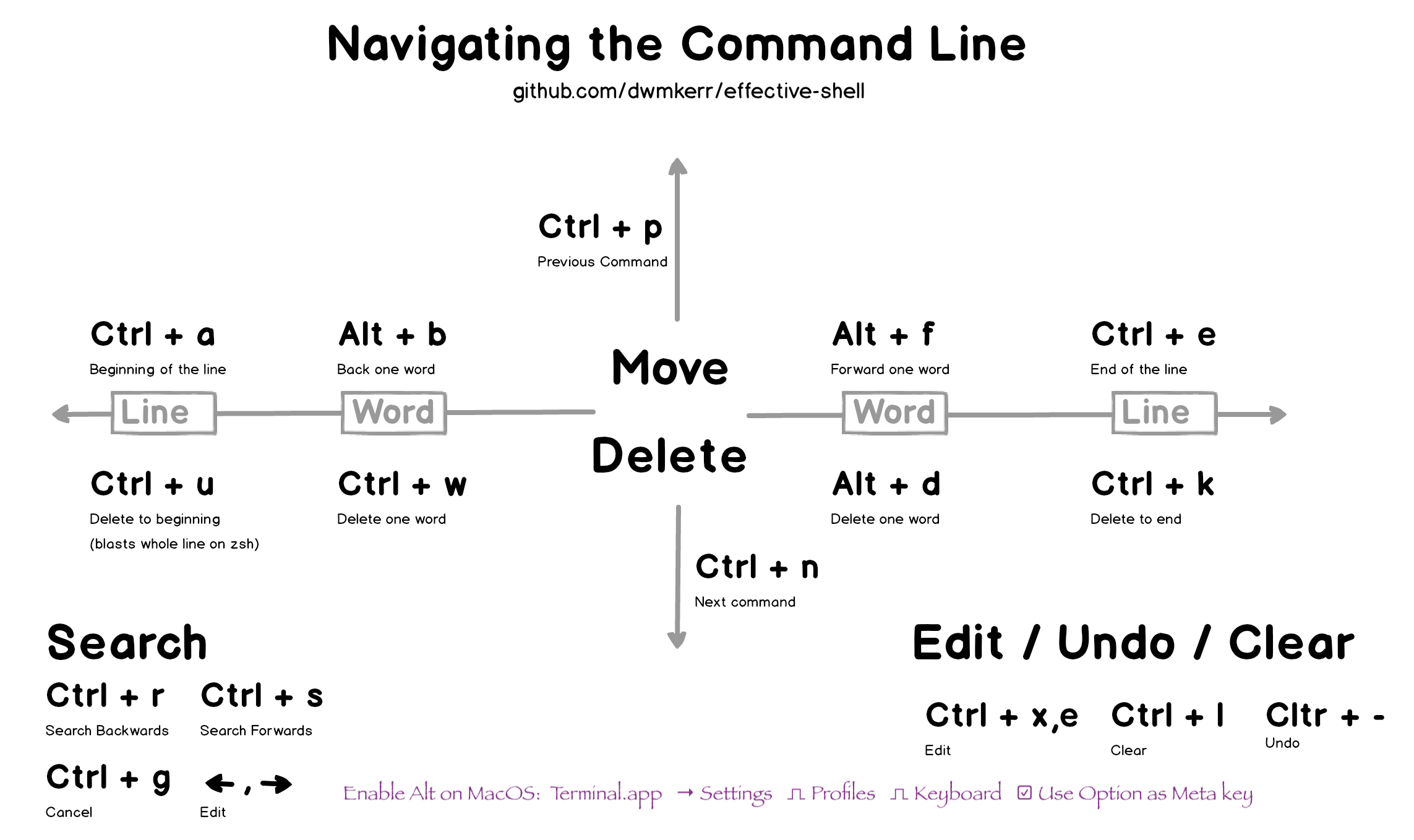

If you want to repeat a command that you’ve run recently, you can access previous commands using the up arrow on your keyboard to go back to the most recent command. Likewise, the down arrow takes you forward in the command history.

A few more useful shortcuts:

- Ctrl+C will cancel the command you are writing, and give you a fresh prompt.

- Ctrl+R will do a reverse-search through your command history. This is very useful.

-

Ctrl+L or the

clearcommand will clear your screen.

There are also keyboard shortcuts to move around on the command line

efficiently.  To learn more,

visit Effective

Shell.

To learn more,

visit Effective

Shell.

You can also review your recent commands with the

history command, by entering:

to see a numbered list of recent commands. You can reuse one of these commands directly by referring to the number of that command.

For example, if your history looked like this:

OUTPUT

259 ls *

260 ls /usr/bin/*.sh

261 ls *R1*fastqthen you could repeat command #260 by entering:

Type ! (exclamation point) and then the number of the

command from your history. You will be glad you learned this when you

need to re-run very complicated commands. For more information on

advanced usage of history, read section 9.3 of Bash

manual.

Exercise

Find the line number in your history for the command that listed all

the .sh files in /usr/bin. Rerun that command.

First type history. Then use ! followed by

the line number to rerun that command.

Examining Files

We now know how to switch directories, run programs, and look at the contents of directories, but how do we look at the contents of files?

One way to examine a file is to print out all of the contents using

the program cat.

Enter the following command from within the

untrimmed_fastq directory:

This will print out all of the contents of the

SRR097977.fastq to the screen.

Exercise

- Print out the contents of the

/broad/hptmp/computing_basics/untrimmed_fastq/SRR097977.fastqfile. What is the last line of the file? - From your home directory, and without changing directories, use one

short command to print the contents of all of the files in the

/broad/hptmp/computing_basics/untrimmed_fastqdirectory.

- The last line of the file is

CCC?CCCCCCC?CCCC?CCC>:CC:C>8C8?97A?'. cat /broad/hptmp/computing_basics/untrimmed_fastq/*

cat is a terrific program, but when the file is really

big, it can be annoying to use. The program, less, is

useful for this case. less opens the file as read only, and

lets you navigate through it. The navigation commands are identical to

the man program.

Enter the following command:

Some navigation commands in less:

| key | action |

|---|---|

| Space | to go forward |

| b | to go backward |

| g | to go to the beginning |

| G | to go to the end |

| q | to quit |

less also gives you a way of searching through files.

Use the “/” key to begin a search. Enter the word you would like to

search for and press enter. The screen will jump to the

next location where that word is found.

Shortcut: If you hit “/” then “enter”,

less will repeat the previous search. less

searches from the current location and works its way forward. Scroll up

a couple lines on your terminal to verify you are at the beginning of

the file. Note, if you are at the end of the file and search for the

sequence “CAA”, less will not find it. You either need to

go to the beginning of the file (by typing g) and search

again using / or you can use ? to search

backwards in the same way you used / previously.

For instance, let’s search forward for the sequence

TTTTT in our file. You can see that we go right to that

sequence, what it looks like, and where it is in the file. If you

continue to type / and hit return, you will move forward to

the next instance of this sequence motif. If you instead type

? and hit return, you will search backwards and move up the

file to previous examples of this motif.

Exercise

What are the next three nucleotides (characters) after the first

instance of the sequence TTTTT quoted above?

CAC

Remember, the man program actually uses

less internally and therefore uses the same commands, so

you can search documentation using “/” as well!

There’s another way that we can look at files, and in this case, just look at part of them. This can be particularly useful if we just want to see the beginning or end of the file, or see how it’s formatted.

The commands are head and tail and they let

you look at the beginning and end of a file, respectively.

OUTPUT

@SRR098026.1 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:968 length=35

NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNCNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN

+SRR098026.1 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:968 length=35

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

@SRR098026.2 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:312 length=35

NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNANNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN

+SRR098026.2 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:312 length=35

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

@SRR098026.3 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:570 length=35

NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNANNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNOUTPUT

+SRR098026.247 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:2:1311 length=35

#!##!#################!!!!!!!######

@SRR098026.248 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:2:118 length=35

GNTGNGGTCATCATACGCGCCCNNNNNNNGGCATG

+SRR098026.248 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:2:118 length=35

B!;?!A=5922:##########!!!!!!!######

@SRR098026.249 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:2:1057 length=35

CNCTNTATGCGTACGGCAGTGANNNNNNNGGAGAT

+SRR098026.249 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:2:1057 length=35

A!@B!BBB@ABAB#########!!!!!!!######The -n option to either of these commands can be used to

print the first or last n lines of a file.

OUTPUT

@SRR098026.1 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:968 length=35OUTPUT

A!@B!BBB@ABAB#########!!!!!!!######Details on the FASTQ format

Although it looks complicated (and it is), it’s easy to understand the fastq format with a little decoding. Some rules about the format include…

| Line | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Always begins with ‘@’ and then information about the read |

| 2 | The actual DNA sequence |

| 3 | Always begins with a ‘+’ and sometimes the same info in line 1 |

| 4 | Has a string of characters which represent the quality scores; must have same number of characters as line 2 |

We can view the first complete read in one of the files in our

dataset by using head to look at the first four lines.

OUTPUT

@SRR098026.1 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:968 length=35

NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNCNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN

+SRR098026.1 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:968 length=35

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!All but one of the nucleotides in this read are unknown

(N). This is a pretty bad read!

Line 4 shows the quality for each nucleotide in the read. Quality is interpreted as the probability of an incorrect base call (e.g. 1 in 10) or, equivalently, the base call accuracy (e.g. 90%). To make it possible to line up each individual nucleotide with its quality score, the numerical score is converted into a code where each individual character represents the numerical quality score for an individual nucleotide. For example, in the line above, the quality score line is:

OUTPUT

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!The # character and each of the !

characters represent the encoded quality for an individual nucleotide.

The numerical value assigned to each of these characters depends on the

sequencing platform that generated the reads. The sequencing machine

used to generate our data uses the standard Sanger quality PHRED score

encoding, Illumina version 1.8 onwards. Each character is assigned a

quality score between 0 and 42 as shown in the chart below.

OUTPUT

Quality encoding: !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJK

| | | | |

Quality score: 0........10........20........30........40..Each quality score represents the probability that the corresponding nucleotide call is incorrect. This quality score is logarithmically based, so a quality score of 10 reflects a base call accuracy of 90%, but a quality score of 20 reflects a base call accuracy of 99%. These probability values are the results from the base calling algorithm and dependent on how much signal was captured for the base incorporation.

Looking back at our read:

OUTPUT

@SRR098026.1 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:968 length=35

NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNCNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN

+SRR098026.1 HWUSI-EAS1599_1:2:1:0:968 length=35

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!#!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!we can now see that the quality of each of the Ns is 0

and the quality of the only nucleotide call (C) is also

very poor (# = a quality score of 2). This is indeed a very

bad read.

Creating, moving, copying, and removing

Now we can move around in the file structure, look at files, and search files. But what if we want to copy files or move them around or get rid of them? Most of the time, you can do these sorts of file manipulations without the command line, but there will be some cases (like when you’re working with a remote computer like we are for this lesson) where it will be impossible. You’ll also find that you may be working with hundreds of files and want to do similar manipulations to all of those files. In cases like this, it’s much faster to do these operations at the command line.

Copying Files

When working with computational data, it’s important to keep a safe copy of that data that can’t be accidentally overwritten or deleted. For this lesson, our raw data is our FASTQ files. We don’t want to accidentally change the original files, so we’ll make a copy of them and change the file permissions so that we can read from, but not write to, the files.

First, let’s make a copy of one of our FASTQ files using the

cp command.

Usually, you would do this in the untrimmed_fastq

directory and the command would look like:

cp SRR097977.fastq SRR097977-copy.fastq

but, because there are a lot of us, lets copy the file from the /broad/hptmp filesystem into our home directory.

START FROM YOUR HOME DIRECTORY

OUTPUT

/home/unix/<username>Confirm pwd says you’re in your home directory

(/home/unix/

BASH

$ cp /broad/hptmp/computing_basics/untrimmed_fastq/SRR097977.fastq SRR097977-copy.fastq

$ ls -FOUTPUT

SRR097977-copy.fastq cb_unix_shell cb_unix_shell.tgzWe now have a copy of the SRR097977.fastq file, named

SRR097977-copy.fastq. We’ll move this file to a new

directory called backup where we’ll store our backup data

files.

Creating Directories

The mkdir command is used to make a directory. Enter

mkdir followed by a space, then the directory name you want

to create:

Moving / Renaming

We can now move our backup file to this directory. We can move files

around using the command mv:

OUTPUT

SRR097977-copy.fastqThe mv command is also how you rename files. Let’s

rename this file to make it clear that this is a backup:

OUTPUT

SRR097977-backup.fastqFile Permissions

We’ve now made a backup copy of our file, but just because we have two copies, it doesn’t make us safe. We can still accidentally delete or overwrite both copies. To make sure we can’t accidentally mess up this backup file, we’re going to change the permissions on the file so that we’re only allowed to read (i.e. view) the file, not write to it (i.e. make new changes).

View the current permissions on a file using the -l

(long) flag for the ls command:

OUTPUT

-rw-rw-r-- 1 jlchang root 879991940 May 1 00:29 SRR097977-backup.fastqNote: your output will show your username where you see

jlchang above.

The first part of the output for the -l flag gives you

information about the file’s current permissions. There are ten slots in

the permissions list. The first character in this list is related to

file type, not permissions, so we’ll ignore it for now. The next three

characters relate to the permissions that the file owner has, the next

three relate to the permissions for group members, and the final three

characters specify what other users outside of your group can do with

the file. We’re going to concentrate on the three positions that deal

with your permissions (as the file owner).

Here the three positions that relate to the file owner are

rw-. The r means that you have permission to

read the file, the w indicates that you have permission to

write to (i.e. make changes to) the file, and the third position is a

-, indicating that you don’t have permission to carry out

the ability encoded by that space (this is the space where

x or executable ability is stored, we’ll talk more about

this in a later lesson).

For more information on Unix file permissions:

https://help.rc.unc.edu/how-to-use-unix-and-linux-file-permissions/

To convert between numeric (eg. 777) and symbolic (eg. rwxrwxrwx) Unix

permissions notation:

https://chmod-calculator.com/

Our goal for now is to change permissions on this file so that you no

longer have w or write permissions. We can do this using

the chmod (change mode) command and subtracting

(-) the write permission -w.

OUTPUT

-r--r--r-- 1 jlchang root 879991940 May 1 00:29 SRR097977-backup.fastqNote: your output will show your username where you see

jlchang above.

Removing

To prove to ourselves that you no longer have the ability to modify

this file, try deleting it with the rm command:

You’ll be asked if you want to override your file permissions:

OUTPUT

rm: remove write-protected regular file ‘SRR098026-backup.fastq'?You should enter n for no. If you enter n

(for no), the file will not be deleted. If you enter y, you

will delete the file. This gives us an extra measure of security, as

there is one more step between us and deleting our data files.

Important: The rm command permanently

removes the file. Be careful with this command (especially if you’re

also using wildcards). It doesn’t just nicely put the files in the

Trash. They’re really gone.

By default, rm will not delete directories. You can tell

rm to delete a directory using the -r

(recursive) option. Let’s delete the backup directory we just made.

Enter the following command:

This will delete not only the directory, but all files within the directory. If you have write-protected files in the directory, you will be asked whether you want to override your permission settings.

Exercise

Starting in your home directory directory, do the following:

- Make sure that you have deleted your backup directory and all files it contains.

- Create a backup of each of our FASTQ files using

cp. (Note: You’ll need to do this individually for each of the two FASTQ files. We haven’t learned yet how to do this with a wildcard.) - Use a wildcard to move all of your backup files to a new backup directory.

- Change the permissions on all of your backup files to be write-protected.

rm -r backup-

cp /broad/hptmp/computing_basics/untrimmed_fastq/SRR098026.fastq SRR098026-backup.fastqandcp /broad/hptmp/computing_basics/untrimmed_fastq/SRR097977.fastq SRR097977-backup.fastq -

mkdir backupandmv *-backup.fastq backup -

chmod -w backup/*-backup.fastqIt’s always a good idea to check your work withls -l backup. You should see something like:

OUTPUT

-rw-rw-r-- 1 jlchang puppet 49504900 May 9 08:09 SRR097977-backup.fastq

-rw-rw-r-- 1 jlchang puppet 111148244 May 9 08:09 SRR098026-backup.fastqKey Points

- You can view file contents using

less,cat,headortail. - The commands

cp,mv, andmkdirare useful for manipulating existing files and creating new directories. - You can view file permissions using

ls -land change permissions usingchmod. - The

historycommand and the up arrow on your keyboard can be used to repeat recently used commands.